One of the most important technical features about IWC has been its use of free-sprung balances on its recent in-house movements.

This has been covered here in some prior discussions, but I’m unsure if its importance has been adequately emphasized nor fully explained. Indeed, even the descriptions of movements on IWC’s website make short shrift of this technical feature. For example, in looking at what IWC says about its in-house movement in the Reference 5101, Portofino Handwound 8-days, at most it mentions that the Calibre 59210’s “indexless balance with its frequency of 28,800 beats per hour helps to ensure a high level of accuracy, as does the Breguet spring, bent into shape in accordance with ancient watchmaking tradition.”

What then is an “indexless” balance and why is it important?

A balance wheel and its balance spring or hairspring are the heart of a mechanical watch. The balance spring is attached inside the balance wheel and controls the speed at which the wheels of the timepiece turn and thus, ultimately the rate of movement of the hands. This is accomplished because the spring reverses the direction of the balance wheel, causing it to oscillate back and forth.

Wikipedia explains this nicely, although technically:

(The balance wheel) “is a weighted wheel that rotates back and forth, being returned toward its center position by a spiral torsion spring, the balance spring or hairspring. It is driven by the escapement, which transforms the rotating motion of the watch gear train into impulses delivered to the balance wheel. Each swing of the wheel (called a 'tick' or 'beat') allows the gear train to advance a set amount, moving the hands forward. The balance wheel and hairspring together form a harmonic oscillator, which due to resonance oscillates preferentially at a certain rate, its resonant frequency or 'beat', and resists oscillating at other rates. The combination of the mass of the balance wheel and the elasticity of the spring keep the time between each oscillation or ‘tick’ very constant, accounting for its near universal use as the timekeeper in mechanical watches to the present.”

Now if this rate is somewhat off, timekeeping will be inaccurate. There are various ways of adjusting rate. The traditional way is to use a “regulator” to adjust the length of the spring. The regulator usually is placed on top of the balance cock (the part that holds the balance wheel in place) and has a narrow slit for which the end of the spring is held. Moving the regulator slides the slit up or down the spring, changing its effective length.

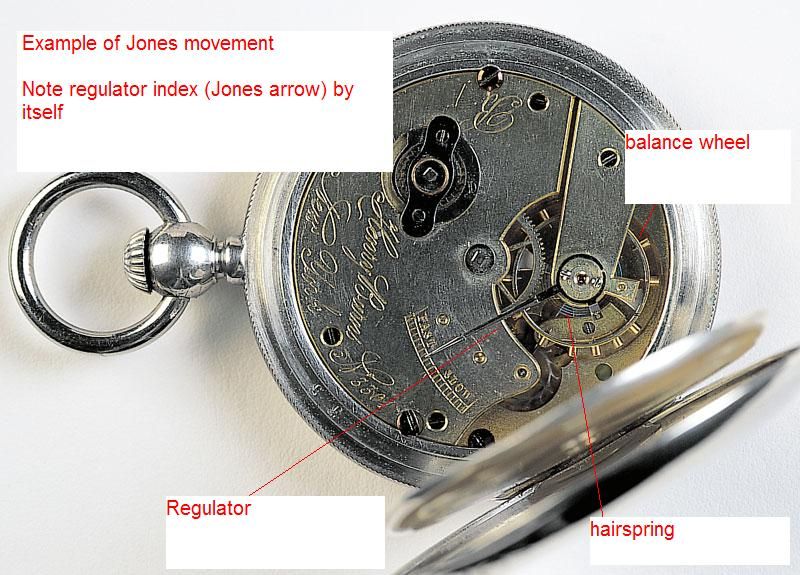

Here’s an example of IWC’s earliest regulator, on a Jones pocket watch movement:

Moving away from the spring's attachment point (“stud”) shortens the spring, making it stiffer and increases the balance's oscillation rate, and thus causes the watch to gain time. Conversely, moving the spring in the other direction lengthens and therefore loosens the spring, causing it to lose time. You can see the indices engraved on most balance cocks as F/S (Fast/Slow) or A/R (Advance/Retard, in French), showing which direction shortens or lengthens the balance spring.

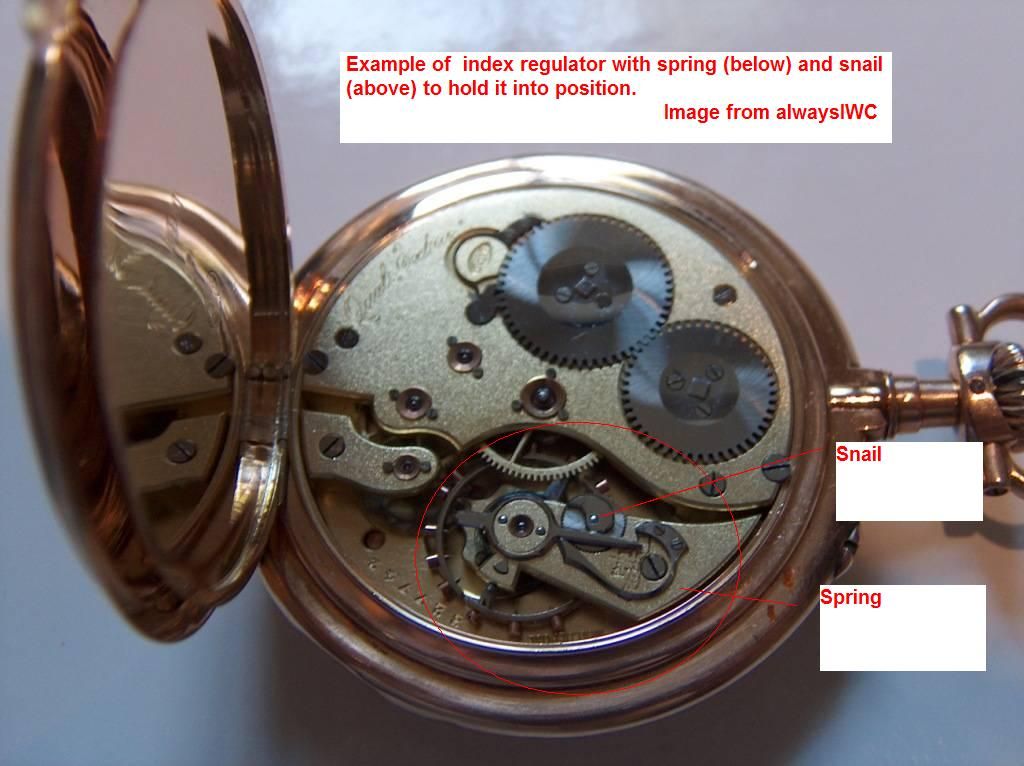

Here’s an example of more sophisticated regulator, with a snail and spring to help hold the index in place:

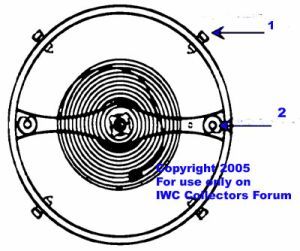

A ‘free-sprung” balance, such as IWC has adopted for its current in-house movements, uses a different system, and one that is more costly and arguably more efficient. Instead of a varying the length of the balance spring to regulate the rate of the watch, a constant length balance spring is used and weights, placed on the balance rim, adjust the oscillating rate of the balance. If you think about it, a heavier weight, or one placed more to the outside of a ring’s rim, will increase the spinning of a wheel.

This is accomplished by special tiny screws (called “macelots” in French) placed all around the circumference of the balance wheel, with somewhat thick heads (to produce weight). Causing these screws to be further away from the rim increases their effect on the spinning balance.

Why use this more elaborate way of regulating weight? The regulator system has some inherent defects, although in modern watches they are relatively small. The spring creates pressure against the regulator lever and therefore over time might cause some minor movement. Essentially a screw keeps the regulator in a constant position. On some watches you can see various forms of counter-screw devices so that the regulator index can’t easily be moved. Perhaps more importantly, a knock against the watch could jar the regulator index lever and cause it to move, causing the rate to change.

On the other hand, the “free-sprung” balance, with no regulator lever changing the length of the hairspring (and indeed a hairspring of constant length), is much harder to knock out of position. As such, a free sprung balance enhances stability of rate.

In addition, I have been told that a free sprung balance produces better positional accuracy.

Being of constant length, it is usually paired with a Breguet overcoil (more on that in a subsequent post). This allows the balance spring to “breathe” concentrically as it contacts and expands as the balance oscillates. Breathing concentrically allows the watch’s rate to be more consistent when placed in different positions.

Incidentally, on some watch movements -often older pocket watches (as in the first two examples) --one will see both screws in the balance and a regulator. This is different, of course, than the true free-sprung balance. The timing screws are used for larger rate changes or poising the balance wheel, but the regulator is used for finer rate adjustments.

If the free-sprung balance is better, then why shouldn’t it be always used by everyone? First, the regulator system has worked relatively well for most watches for way over a century. The differences are, by and large, marginal for most. However, many of IWC’s in-house movements today have large main springs (different than balance or hair springs). These large springs, such as those used in the Portofino 8-day, produce a fair amount of force, and therefore can cause some isochronism error. Any system that produces better rate stability is important, and the free-spung balance helps. Regardless, most watchmakers believe that the free-sprung balance produces better results over a longer period of time.

However, free spung balances are more difficult to set-up, and more difficult to regulate.

Instead of adjusting a balance spring’s position and length, each of the screws around tthe rim of the balance have to be precisely twisted for exactly the right overall weight. Moreover, they all have to be adjusted symmetrically: any non-symmetric adjustment will cause the balance wheel to get out of poise, and wobble --just like a bicycle wheel where the spokes aren’t all tuned. But once properly set up, they’re more difficult to get out of position.

The real issue, from a manufacturing perspective, is that free-sprung balances are more expensive to produce. They are more difficult to set-up, but they have real benefits.

Many high-end manufactures, such as Patek and Audemars Piquet (and even Rolex) now use free-sprung balances. IWC does, too, on its in-house movements, and it is to their credit. But

IWC scarcely even advertises this important technical feature. All it says is that there’s an “indexless balance”. That means, in actuality, that there’s no regulator, and that’s because of a system using a free-sprung balance.

These technical details for many consumers don’t sell more watches. It’s arguable whether the free-sprung balance reflects a valuable marketing point. But here it demonstrates not only the technical ability and attention to detail embodied in these IWC movements, but also the dedication to producing the highest quality product, even if the cost is higher.

Comments and questions, and corrections too, are invited. After all, I’m not a watchmaker. :)